Thursday 19 May 2011

This is a late response to Bob’s 2010 booklist post, but rather than list off a few of the few books I read last year, I’d like to talk about three of them that tell a sort of shared story: a children’s picture book, a fat novel, and a journalist’s book on China.

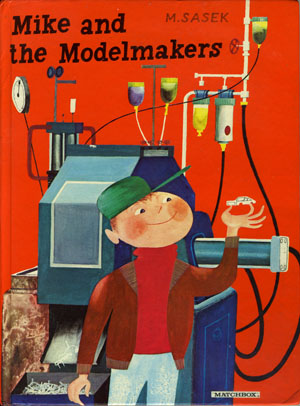

Miroslav Sasek has enjoyed a posthumous boom in recent years, with his colourful travel books for children in every bookshop window, but a book unlikely to be reprinted is Mike and the Modelmakers, a picture book published in 1970 by Lesney Products & Co. Ltd, the then London based manufacturer of Matchbox model cars.

I was lucky enough to find a secondhand copy of this last year at Gosh! Comics on Great Russell Street.

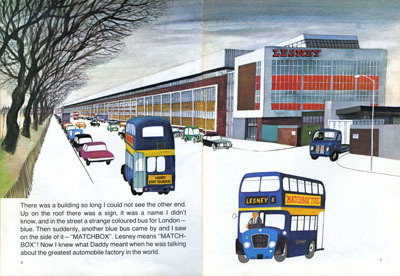

Lesney Products began as a small die casting company in 1947, developed the Matchbox line in the 1950s, and expanded massively over the following decade.

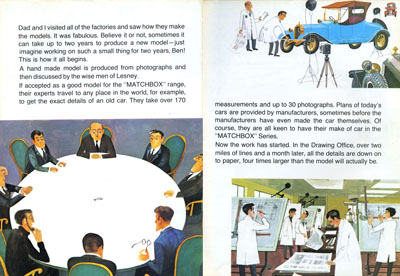

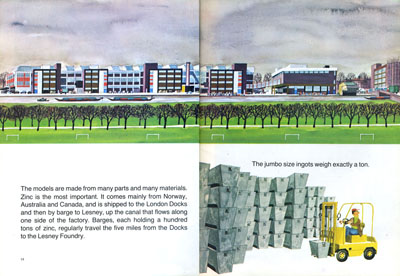

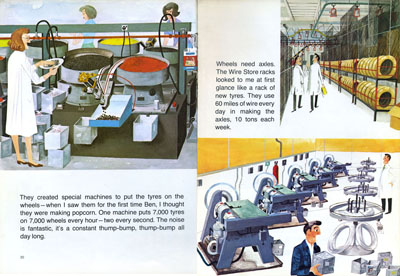

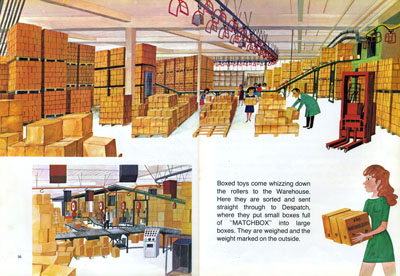

The book shows in great detail the design and manufacturing process at the company’s Hackney site, where six factories produced more than a million Matchbox models a day, according to the M. Sasek book. A company history at Frank’s Matchbox Lesney Page gives companywide figures: “By 1969, Lesney made 5,500,000 models per week, exported to 130 countries, with 40% going to the USA, and employed some 6,000 people in 12 London factories.” But this was to be the company’s high-water mark, followed by increasingly tough competition, industrial action, and worldwide economic change, until in 1982 Lesney went bankrupt and into receivership. The Matchbox brand was sold, and tooling and production moved to Macau, then later to Shanghai.

The site of the main factory at Lee Conservancy Road, opposite Mabley Green, pictured above, was redeveloped as housing some years ago. Another factory, on the north side of Homerton Road, was demolished at the end of 2009. An apartment block is now near completion on that site.

The story of Lesney was echoed in another book I read last year, Philip Roth’s American Pastoral. This was the first Roth novel I’d read, though I didn’t quite make it to the end. The main event of the plot is a fatal Weathermen-type bomb explosion, detonated in 1968 by the only daughter of a nice middle class New Jersey couple. Surrounding that is a wider description of social, political and economic changes from the 1940s to the 1990s, focusing on human aging, on internal mass migration in the US, on ethnic conflict and ethnic assimilation, on globalisation.

The main character is Seymour ‘the Swede’ Levov, father of the bomber and heir to his family’s big glove manufacturing business in Newark,. He grows up in an overwhelmingly Jewish urban neighborhood but marries an Irish American and aspires to a wholly secular country life, daydreaming of himself as Johnny Appleseed. His daughter then makes her more violent break with the past, taking a life, and shattering the family.

This personal disintegration is paralleled by the vanishing of the seemingly stable Jewish community of Seymour’s childhood, the area becoming an African American neighborhood in the Great Migration, and then the vanishing of Newark’s seemingly solid manufacturing industry, including the Levov family’s glove making business which moves manufacturing overseas.

There is a lot about the glove business in American Pastoral, about how business is done small scale and big scale, and on the technicalities of manufacture. At one point the Swede leads another character on a tour of the factory that feels as detailed as the tour of Lesney in the Matchbox book. Central in the description of the changes in the business over the years is a reiteration of how the social, economic, and technological changes lead to a loss of detailed knowledge of the product in workforce and management, a loss of craftsmanship and connectedness.

That wider social and economic background is so vividly described in American Pastoral that it feels more interesting to me than the social and political changes possessing the central characters. Though these are related, it seems as if a narrative of symptoms is distracting the characters from greater causes.

This distraction reaches its peak at the end of the novel, an extended dinner party where the pretensions of the Swede’s guests become unbearable, the various interpersonal disasters become increasingly grotesque, and the symptoms overwhelm entirely. Here, despite my sympathy with its choice of targets, I fell out of engagement with the book.

A third book with a shared interest in economic change, migration and globalisation, is Peter Hessler’s Oracle Bones.

The book covers his time as a journalist in China from 1999 to 2002, and while job demands that he cover headline events like the bombing of the Chinese Embasy in Belgrade, the collision between a Chinese fighter jet and a US electronic eavesdropping plane, and preprations for the Beijing Olympics, but finds that he doesn’t make a good fit as a newspaper reporter:

I worked slowly; I dreaded deadlines; I failed to cultivate contacts.Or failed to cultivate the right kind of contacts:

I quoted everybody that a good journalist doesn’t quote: cabbies, waitresses, friends. I spent a lot of time in restaurants. I avoided press conferences. I loathed talking on the telephone - a crippling neurosis for a newspaper reporter. In particular I hated staying up late at night to call American academics so they could give me a quote about what was happening in China. I already knew what was happening: normal people were asleep.

Peter Hessler also questions how useful it is to focus primarily on dramatic human rights stories when writing pieces for an American audience unable to directly affect events in an increasingly powerful and independent China.

The articles appeared in American newspapers, where the readers couldn’t solve the problems and didn’t have the background necessary to keep everything in context. [...] And there is a point at which even the best intentions become voyeurism.

His book then takes a much more rambling look at China. One strand follows archaeological research into the oracle bones of the title, a thread that leads to the politics of denunciation under the Cultural Revolution.

Another story follows an Uighur friend who goes to the US seeking political asylum, going from a life as a successful trader in China to working delivering takeaways for a restaurant in Washington DC.

A third story is about film actor and director Jiang Wien, a mix of showbiz larks and the politics of Chinese nationalism.

The central story, though, is the massive ongoing economic change in China. Thanks to economic liberalisation, the spread of manufacturing technology, and the invention of container shipping, this is where the toy manufacturing business and the glove manufacturing business has gone to.

Peter Hessler had earlier worked as an English teacher, and Oracle Bones draws on his continued contact with a number of his former pupils to build an image of China’s new economy as seen by some of the workforce. It’s a picture too detailed to summarise here, but one passage stuck with me: the story of the father of one of his pupils, Willy.

In Willy’s first year of life, Chairman Mao died, and on hearing the news, Willy’s father, a construction worker, lay awake all night, certain that all would now change, but unable to predict how.

Willy’s father was right about the changes. Although he was illiterate - he hadn’t attended a single day of school in his life - he was naturally intelligent, and he responded quickly when the economic reforms filtered down to the village. By the early 1980s, he was organising private construction crews to work in Double Dragon Township. By the time Reform and Opening was five years old, Willy’s family had become one of the most prosperous in Number Three Production Team.

Also at the start of the 1980s, the first residents of Willy’s village joined the internal migrants moving to find work, and the first television appeared in the village.

But in a very short time, it became hard for them to keep pace with change.

By the time Willy was ten years old, Reform and Opening had already begun to leave his father behind. The new economy changed so fast that windows of opportunity were brief - sometimes a certain product or a particular set of skills were valuable only for a year or two. In the early 1980s, native intelligence and diligence were adequate for small-scale construction work, and Willy’s father flourished. But soon there was more competition, and bidding for projects required shrewd calculation. Sometimes Willy’s father organised a long job and actually lost money. He often warned Willy about the disadvantages of being uneducated: “My father said it was too bad to work without education; he said you would be cheated by anybody who is literate, who knows something. If you don’t study, you will just be a coolie.”

Thanks to Enda for giving me Oracle Bones . . .

. . . and thanks to John Dog for American Pastoral.

Mike and the Modelmakers copyright © 1970 Lesney Products & Co. Ltd